Insecticide seed treatments are not always economical in Mid-Atlantic grain production.

Insecticide seed treatments are not always economical in Mid-Atlantic grain production.[/box] Neonicotinoid insecticide seed treatments (NSTs) are widely used in grain production. As of 2012, NSTs were used on 34-44% of soybeans and almost all corn grown in the U.S. Because the active ingredient is absorbed by the seed and travels through the plant as it grows, NSTs protect crops from many early season soil and seedling pests, which can be difficult to target through other means. However, they only provide protection for 3-4 weeks after planting. The management decision must be made at the time of planting, before the season’s insect pressure can be measured. For these reasons, NSTs do not always provide economic benefits, especially when early season pest pressure is lacking. NSTs can also impact non-target beneficial organisms, including arthropod natural enemies, pollinators and earthworms. The widespread and repeated use of NSTs also increases the likelihood of pests developing resistance to them.

Click here for a fact sheet about NST use in soybean production.

Aditi Dubey, Galen Dively, and Kelly Hamby from the Department of Entomology, University of Maryland, conducted a three-year study to better understand both the benefits and risks of using two neonicotinoid seed treatments, Cruiser® 5FS (thiamethoxam, Syngenta) and Gaucho® 600 Flowable (imidacloprid, Bayer) in a 3-year grain crop rotation of full-season soybean, winter wheat, double-cropped soybean and corn, from 2015 to 2017.

Aditi Dubey, Galen Dively, and Kelly Hamby from the Department of Entomology, University of Maryland, conducted a three-year study to better understand both the benefits and risks of using two neonicotinoid seed treatments, Cruiser® 5FS (thiamethoxam, Syngenta) and Gaucho® 600 Flowable (imidacloprid, Bayer) in a 3-year grain crop rotation of full-season soybean, winter wheat, double-cropped soybean and corn, from 2015 to 2017.

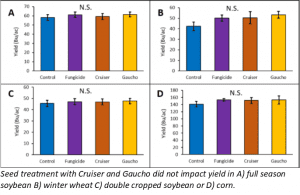

The effects of NSTs on pest and beneficial insects, as well as on yield were evaluated. Overall, pest pressure remained very low throughout the study, and never approached treatment thresholds.

“We did see an early season reduction in pests in full-season soybean and wheat,” Hamby reported. “However, the use of NSTs did not impact yield in any of the crops, and the NSTs also reduced natural enemies in soybean.”

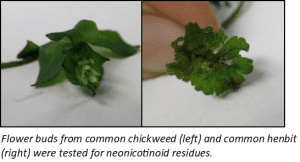

To evaluate whether neonicotinoids that remain in the soil after NST use can be taken up by other plants, buds were collected from weedy winter annual plants (common chickweed and common henbit) growing within the treatment plots in 2016 and 2017, and neonicotinoid residues were measured. Uptake into winter annual flowers could expose pollinators; however, in this case, no evidence was found that neonicotinoids from NSTs are taken up by winter annual flowers. Data is still being processed from this study, with more information coming about the impact of NSTs on soil and litter dwelling arthropods, as well as their effects on soil microbial communities.

“Our results so far indicate that NSTs provide limited pest protection, as they are only effective early in the growing season,” Hamby stated.

When pest pressure is low, the use of NSTs does not increase yield relative to untreated seeds. NSTs can be a useful tool for insect pest management in grain crop production. When pest pressure is high, they provide a convenient and economical way to protect crops. However, this research demonstrates that the use of NSTs is not always economically beneficial in the Mid-Atlantic region. Producers can make the best use of NSTs by using them in fields that regularly have high early season insect pest pressure.

Click here to learn more about this research project.

This research has been funded by the Maryland Soybean Board, the Maryland Grain Producers Utilization Board and Northeast SARE. Outreach efforts associated with this project were supported by the Crop Protection and Pest Management Program [grant. no 2017-70006-27171/project accession no. 1013913] from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.